3 Healthcare Strategies Expats Use Abroad (And Which One Fits You)

Forget "best healthcare country" promises. Learn how to evaluate any country yourself.

I read another “best healthcare abroad” article last weekend.

France was #1. Portugal #2. Spain #3.

Useless.

France reimburses 70% of medical costs through its public system. But you need to be a legal resident for three months before you’re eligible.

Portugal has public healthcare too, but most expats pay for private insurance their first few years because the public waitlists are long.

Spain lets you into the public system faster, but coverage varies wildly by region.

Ranking these countries 1-2-3 tells you next to nothing.

Because the systems work completely different.

System #1 for one person might be #3 for another.

As I said. Useless.

Here’s what we’ll cover today:

3 healthcare strategies expats actually use abroad

Which expat profile fits each one

The traps that catch people in each approach

Let’s get into it.

The 3 Strategies

My #1 advice for you:

Do not pick “healthcare system”.

Pick a “healthcare strategy”.

This form of thinking does not only work for healthcare, but also for deciding on which country to move to or how to structure your banking abroad.

It’s all about 1) understanding your situation/needs and 2) having a backup.

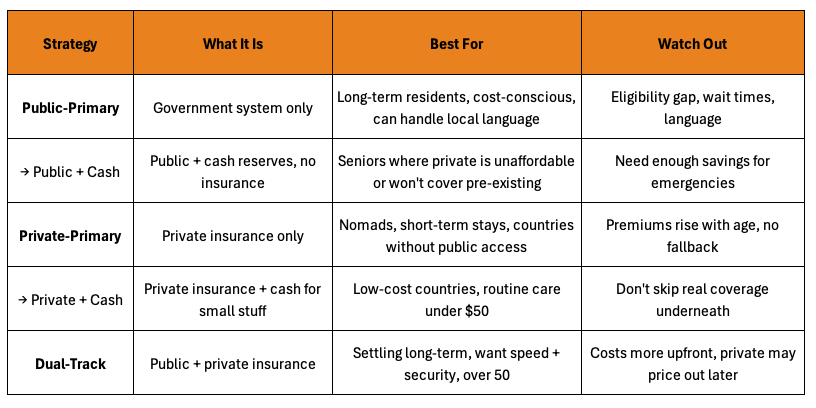

Here are the 3 strategies expats actually use:

1. Public-Primary

Public is your ONLY system. You might add a “top-up” (like France’s mutuelle) that covers the 30% the public doesn’t reimburse. But you’re not carrying a separate private insurance policy. All your care flows through the public system.

2. Private-Primary

Private insurance is your MAIN coverage. Either no public option exists for foreigners, or you don’t qualify yet, or you prefer private anyway. This is how expats handle Thailand, UAE, Mexico, or Singapore.

3. Dual-Track

You maintain TWO complete, parallel systems. A full private insurance policy AND public enrollment. You choose which door to walk through depending on the situation. Need a fast MRI? Private. Emergency surgery at 2am? Public.

Each approach has trade-offs.

None is “the best.”

The right one depends on your age, health, budget, and how long you’re staying.

Let’s break them down.

Planning to retire abroad in the next few years? Reply “RETIRE” and I will add you to my “Retire Abroad Priority List” where I share my best tactics for retiring abroad.

Strategy 1: Public-Primary

You join the government healthcare system. Public is your foundation.

This is how most locals get healthcare in Europe, Canada, and Australia.

The government covers most costs, funded by taxes or social security contributions. You pay little or nothing at the point of care. In France, the public system reimburses 70% of costs. In the UK, most care is free. In Canada, hospital visits and doctor appointments cost nothing out of pocket.

The catch

You need legal residency. And there’s usually a waiting period.

France requires three months of legal residence before you can apply for PUMA, the public system.

Canada varies by province. Ontario and British Columbia both require three months. Quebec has no waiting period.

Spain ties eligibility to social security contributions, so you need to be employed or self-employed and paying into the system before you qualify.

This strategy fits long-term residents who plan to stay years, are cost-conscious, and can navigate bureaucracy in the local language.

It doesn’t fit digital nomads moving every few months, anyone who needs care immediately upon arrival, or people who need English-speaking doctors guaranteed in non-English first countries.

The traps

Watch out for those traps.

1/ The eligibility gap

The eligibility gap is the big one. You land in your new country. The public system requires three months of residency before you can enroll.

What happens if you get sick in month two? You pay cash or you need private insurance to bridge the gap. Most expats don’t plan for this.

2/ Wait times

Public systems prioritize by urgency, not convenience. A broken arm gets seen immediately, while a dermatology appointment might take two months, and a knee surgery might take 6.

3/ Language

The third trap is language. Public systems operate in local language. Forms are in French. Doctors speak Spanish. Nurses explain things in German. Yes, there are English-speaking doctors, but don’t rely on this in public systems.

4/ Age

The fourth trap is about age. You need private insurance to survive the eligibility gap. But private insurers have age limits and premiums spike after 60.

I will go into detail on this in the specific age section below.

How to do this the right way?

Example: A retired couple moves to France on a long-stay visa. They budget for private insurance during the three-month waiting period.

Once eligible, they enroll in PUMA and add a mutuelle (top-up insurance) for €100 per month. Their out-of-pocket costs drop to nearly zero.

This is Public-Primary done right.

Takeaway: Public-Primary works if you’re staying long-term and can survive the eligibility gap.

Strategy 2: Private-Primary

No public system? No problem.

Private insurance is your entire healthcare plan.

This is the default in countries where foreigners can’t access government healthcare.

The UAE has no public option for expats at all.

Singapore’s public system is reserved for citizens and permanent residents.

Thailand excludes non-employed foreigners from its Universal Coverage Scheme.

In these countries, private insurance is the preferred option for most.

But some expats choose Private-Primary even when public exists.

Reasons for this choice are often:

Shorter wait times.

English-speaking doctors.

Less exposure to local bureaucracy.

If you’re only staying one or two years, the hassle of enrolling in a public system might not be worth it.

Private means less paperwork and coverage on day one.

This strategy fits digital nomads, short-term assignees, and anyone in a country without public access for foreigners.

Retirees can use it too, but know the risks: premiums rise every year, and you have no fallback if you age out of coverage or hit policy limits.

The cash-pay tactic

In low-cost countries, smart expats combine private insurance with cash payments for routine care.

A dental cleaning in Thailand costs $20-30. A basic checkup around $30 to $50. Blood work is similarly cheap. Filing an insurance claim for these amounts might not be worth the paperwork.

You pay cash for the “small things” and save your insurance for hospitalizations, surgeries, and emergencies. This keeps your relationship with the insurer clean and avoids the hassle of reimbursement forms for every checkup.

The trap

Underinsuring. Some expats get so comfortable paying cash and skip comprehensive coverage entirely. Then they need a $40,000 surgery and have nothing.

Cash-pay works as a tactic, not an entire strategy.

You still need real insurance underneath.

Example: I live in Bangkok. I carry private insurance with a small deductible that covers everything major. Dental cleanings, blood work, routine checkups? I pay cash. They’re too cheap to bother filing claims. But when something serious happens, I use my policy and can walk into any hospital in the city, including the best ones.

That flexibility is worth the premium.

My insurer doesn’t raise premiums, because my claim history is not filled with plenty of small claims.

Takeaway: Private-Primary is your only option in some countries and the simplest option in others, but premiums compound over time.

Strategy 3: Dual-Track

Why choose one system when you can have both?

Dual-Track means you enroll in public healthcare AND carry private insurance.

Two separate systems, used strategically:

Need a quick MRI? Private.

Emergency surgery at 2am? Public.

Private policy maxed out on a chronic condition? Public as backup.

You pick the insurance depending on the situation.

This works in countries where public systems accept foreigners but have limitations “worth bypassing”.

Portugal, Costa Rica, Panama, and Cyprus all allow this setup. You pay into the public system through taxes or contributions. You add private insurance on top. The result is flexibility that neither system offers alone.

The obvious question:

Why pay for both?

In some countries, the public cost is so low it’s almost negligent not to enroll.

In Cyprus, the public healthcare contribution (GESY) is 2.65% of your income. Pay yourself a €19,000 salary and €50,000 in dividends, and your public healthcare costs roughly €150 per month.

Add private insurance on top and you get two systems instead of one. The private portion varies by age, but the public cost is fixed.

Why this instead of “Private-Primary”?

Public handles the things private insurers hate.

Chronic conditions.

Pre-existing issues after your first year.

Long-term care that drags on for years.

Private policies have lifetime limits. Public doesn’t. If your private insurer denies a claim or drops you at renewal, public catches you.

No single point of failure.

Private handles the things public systems do poorly.

Speed.

Same-day appointments.

English-speaking doctors.

Private hospitals with nicer rooms.

You’re not stuck waiting two months for a specialist because the public queue is long.

The trap is assuming public is your primary.

It’s not.

Use private for your regular care. Public is your backup.

If you flip that and try to use public for everything, you’ll have the same wait times and language barriers as “Public-Primary”.

Example: When I lived in Cyprus, I enrolled in GESY as a non-domiciled resident. My contribution was 2.65% of salary and dividends. Roughly €150 per month.

I added international private insurance on top. When I needed something fast, I walked into a private hospital and used my private policy.

But I always had public underneath in case something long-term came up.

Takeaway: Dual-Track costs slightly more than private-only but gives you two systems instead of one. Worth it when you’re staying long-term and the public system is cheap enough to just enroll.

Stuck on your moving abroad process? You can book an hour with me here.

The Age Factor

Everything changes after 50.

Not because public systems care about your age (most don’t). France PUMA has no age limit. Spain actually has a pathway specifically for residents over 65.

The problem is private insurance.

Private insurers see age as risk. The older you are, the more likely you will file claims.

So they respond in three ways:

Enrollment limits

Higher premiums

Stricter underwriting

Premiums start climbing around 50.

By 60, you’re typically paying two to three times what a 40-year-old pays for the same coverage. Some international policies for seniors over 65 run €5,000 or more per year for hospitalization alone.

That’s before deductibles and co-pays.

Underwriting gets tighter too. Pre-existing conditions that might get covered at 45 get excluded at 60.

Diabetes.

High blood pressure.

A history of anything cardiac.

Insurers either exclude these conditions entirely or load your premium with surcharges.

Then there are enrollment limits:

Sanitas in Spain caps new members at 75.

AXA caps at 80 (with exclusions after that).

Some insurers won’t write new policies after 65 without continuous prior coverage.

Not every insurer has these limits. But your options narrow as you get older, and the insurers willing to cover you charge accordingly.

What this means for each strategy

Public-Primary becomes the only realistic option for many seniors.

No fighting with insurers. All you need is to “survive” the eligibility gap. The challenge is bridging that gap with private coverage before enrollment limits kick in.

Private-Primary gets harder with age.

Premiums compound. If your only plan is private insurance, you’re betting that an insurer will keep covering you at a price you can afford. Few will, most won’t (we’re talking about insurance companies after all).

Dual-Track is the safest (but increasingly expensive) play for anyone over 50.

Lock in private coverage while your options are still wide. Enroll in public as backup. If private gets too expensive or you age out of your plan at 75, you still have public.

Example: A 58-year-old moves to Portugal. She enrolls in the public system (SNS) immediately. She also buys private insurance while she’s still under 60 and healthy. By 70, her private premiums have doubled.

By 75, she decides to drop private and rely on public alone. She can, because she enrolled in both 17 years earlier. If she’d waited until 70 to figure this out, her private options would have been limited and expensive.

Another tweak to think about (especially in low cost countries):

When private insurance stops making sense, some retirees go “Public + Cash” (similar to what I described doing myself in “Strategy 2: Private-Primary”, but with Public instead of Private). Use the public system and keep cash reserves for private care when needed. If you are eligible for public insurance in your target country, this is another smart way to go about things.

Conclusion

That’s it.

Now you can skip the “Best Healthcare Abroad” rankings.

You have:

Three strategies.

Two nuances.

One framework you can apply to any country:

Public-Primary works when you’re staying long-term, can survive the eligibility gap, and don’t mind operating in the local language. It’s also the cheapest option.

Private-Primary works when you are moving frequently, the country excludes foreigners from public care, or you want maximum flexibility. Just know that premiums rise with age and there’s no fallback if your insurer drops you.

Dual-Track works when you’re settling somewhere with an accessible public system and want both speed and security. It costs more upfront but removes the single point of failure.

Hope this helped.

Appreciate you being here,

— Ben

PS

If you are between 50-75 and want to emigrate within the next 0-5 years, and don’t want to navigate healthcare (and banking, visas, taxes and country selection) by yourself, reply to this mail with “Retire” to get a private invite to the “Retire Abroad Priority List”.

PPS

My grandmother is 85. Covered by German public healthcare her whole life. No premiums. No age limits. That’s what a good system looks like.

Ben, this is absolutely amazing information for anyone from abroad. I wish I'd had this when I lived in Japan. Even now, that I found it really helpful for some people living in the UK as it reminds me why I'm on a dual-track programme for healthcare. Thank you for this excellent work.

Ben - I can't thank you enough for this information. We will definitely use this information. Your Retire group is a lifesaver. Thanks again!